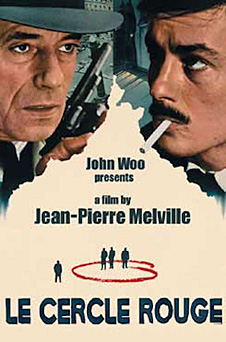

LE CERCLE ROUGE

Special Presentation (digitally restored) • Drama • France, 1970

DCP • 1:85 • Dolby Digital 2.0 • Color • 140 min

Written and directed by: Jean-Pierre Melville

Cinematography: Henri Decae

Film Editing: Marie-Sophie Dubus

Original Score: Eric Demarsan

Produced by: Robert & Jacques Dorfmann (Les Films Corona)

Cast: Alain Delon (Corey), Bourvil (Inspector Mattéi), Gian Maria Volonté (Vogel), Yves Montand (Jansen), François Périer (Santi)

U.S. Distributor: Rialto Pictures, Criterion

In celebration of the 100th anniversary of Jean-Pierre Melville, the filmmaker who transformed the crime thriller into high art, COLCOA is proud to present his most acclaimed picture, Le Cercle Rouge. With a formidable cast including Alain Delon, Yves Montand, and Bourvil, the boilerplate plot involves a suave criminal mastermind, a vicious escaped convict, a washed-out ex-cop with a knack for hitting bulls-eyes before he started hitting the bottle, and a relentlessly nasty, cat-loving detective methodically hunting them down before they can knock off a prominent jewelry store on Place Vendome. Ostensibly a heist movie, what elevates it is the Melvillian flourishes – finely-honed visuals, poignant fatalism, and an explicit code of honor and loyalty. In Melville’s universe, a Gauloise cigarette is as essential as a gun, and which side of the law you’re on is less important than whether or not you betray trust. Another signature touch, balletic precision, is on glorious display in the film’s 20-minute show-stopping robbery sequence. Presented with the World Premiere of Melville’s restored first film, 24 hours of a Clown’s Life.

1970 was a very good year for writer/director Jean-Pierre Melville. Le Cercle Rouge had just crowned a string of successes including Le Samouraï (1967) and Army of Shadows (1969). Melville’s recent box-office triumph might have surprised some: after all, his films were often bleakly pessimistic, his characters could be grimly laconic, and their endeavors, no matter how heroic in effort, often came to pointless ends. Known mostly for his gangster epics like Bob le Flambeur (1955), Melville re-imagined the criminal world as a battleground of moral and philosophical ideas, much the same way the West had functioned in American cinema. In this arena, a man’s conduct was beyond the dictates of state and law, subject to something more essential within him. It is possible that Melville’s preoccupation with honor began in WWII, during which he fought in the French Resistance. For him, the resistance fighter and the gangster both live in a kind of underworld where loyalty is the primary currency. Sadly, despite the ringing kudos of 1970, Melville would go on to complete only one more film, Un Flic (1972), a lackluster effort that he would disown shortly before his death in 1973.